Jessica Meir's return wasn't like that.

"We called it the planes, trains and automobiles version of trying to get back home," Meir said.

The drastic measures were taken because of the coronavirus pandemic, which Meir, Morgan and Russian cosmonaut Oleg Skripochka observed from the International Space Station until they returned home this month. Border closings and other travel restrictions caused by the pandemic forced NASA and Russia's space agency to alter the standard recovery process.

Meir returned to a world different from the one she left about seven months ago.

"I wasn't really ready to leave," Meir said. "I would have loved to stay up there longer, and especially coming home to a completely different planet like the one we've returned to. It's an interesting transition."

Moments after Meir landed April 17 after more than 200 days in space, she was whisked aboard a helicopter for a three-hour flight to the city of Baikonur in southern Kazakhstan. From there, Meir and fellow NASA astronaut Andrew Morgan spent three more hours being driven to a nearby city for their flight back to Houston.

"We called it the planes, trains and automobiles version of trying to get back home," Meir said.

The drastic measures were taken because of the coronavirus pandemic, which Meir, Morgan and Russian cosmonaut Oleg Skripochka observed from the International Space Station until they returned home this month. Border closings and other travel restrictions caused by the pandemic forced NASA and Russia's space agency to alter the standard recovery process.

Meir returned to a world different from the one she left about seven months ago.

"I wasn't really ready to leave," Meir said. "I would have loved to stay up there longer, and especially coming home to a completely different planet like the one we've returned to. It's an interesting transition."

Once back in the U.S., Meir and Morgan entered a weeklong quarantine at NASA's Johnson Space Center. A short period of separation is standard, but because astronauts on long-duration spaceflights typically experience changes to their immune systems, NASA enforced a prolonged quarantine to protect the two astronauts from any Earth-bound pathogens.

"Something about that spaceflight environment does have a direct influence on our immune system, and that's why they wanted to be extra conservative with what we were exposed to first upon coming back," Meir said, adding that returning astronauts are physiologically similar to people with compromised immune systems.

Still, she said, being back home has made the pandemic more real for her. Although she had access to the news aboard the space station and was in regular contact with loved ones, the crew's day-to-day operations continued mostly uninterrupted.

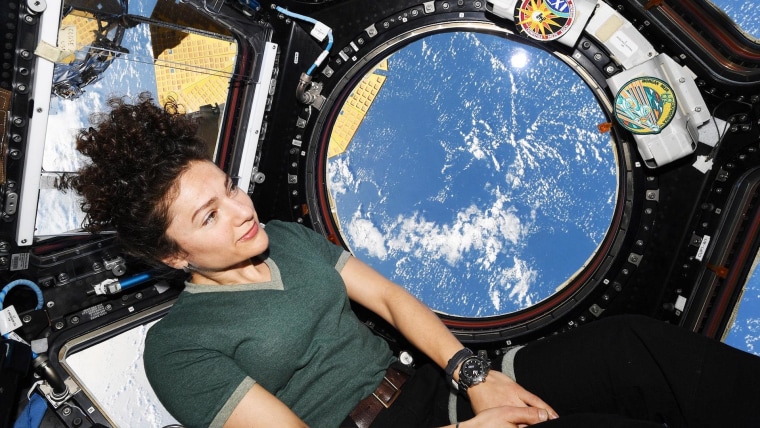

"It really was this stark contrast, because, of course, the Earth didn't look any different to us," she said. "It looked just as gorgeous, equally as stunning, as it had before everything happened. And to then think about what was going down on the surface and that every person, all 7½ billion people on the planet, were being affected by this and only three of us who were in space at the time weren't. That was really difficult to comprehend, as well, that we were the only three individuals that it wasn't affecting our lives in some way."

But Meir said that looking back at the planet from the station's orbital perch did offer a unique perspective on the unfolding situation, and she cited examples of astronauts who were in space during other major events in history, including the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001.

When astronauts return to Earth, they're usually given a chance to sit and adjust to being back in Earth's gravity. Plummeting through the atmosphere can make for a rough ride, so after crew members are pulled from their capsule, they are taken to a staging area where they can relax as medical officers perform routine check-ups.

Jessica Meir's return wasn't like that.

Moments after Meir landed April 17 after more than 200 days in space, she was whisked aboard a helicopter for a three-hour flight to the city of Baikonur in southern Kazakhstan. From there, Meir and fellow NASA astronaut Andrew Morgan spent three more hours being driven to a nearby city for their flight back to Houston.

"We called it the planes, trains and automobiles version of trying to get back home," Meir said.

The drastic measures were taken because of the coronavirus pandemic, which Meir, Morgan and Russian cosmonaut Oleg Skripochka observed from the International Space Station until they returned home this month. Border closings and other travel restrictions caused by the pandemic forced NASA and Russia's space agency to alter the standard recovery process.

Meir returned to a world different from the one she left about seven months ago.

"I wasn't really ready to leave," Meir said. "I would have loved to stay up there longer, and especially coming home to a completely different planet like the one we've returned to. It's an interesting transition."

Once back in the U.S., Meir and Morgan entered a weeklong quarantine at NASA's Johnson Space Center. A short period of separation is standard, but because astronauts on long-duration spaceflights typically experience changes to their immune systems, NASA enforced a prolonged quarantine to protect the two astronauts from any Earth-bound pathogens.

"Something about that spaceflight environment does have a direct influence on our immune system, and that's why they wanted to be extra conservative with what we were exposed to first upon coming back," Meir said, adding that returning astronauts are physiologically similar to people with compromised immune systems.

Still, she said, being back home has made the pandemic more real for her. Although she had access to the news aboard the space station and was in regular contact with loved ones, the crew's day-to-day operations continued mostly uninterrupted.

"It really was this stark contrast, because, of course, the Earth didn't look any different to us," she said. "It looked just as gorgeous, equally as stunning, as it had before everything happened. And to then think about what was going down on the surface and that every person, all 7½ billion people on the planet, were being affected by this and only three of us who were in space at the time weren't. That was really difficult to comprehend, as well, that we were the only three individuals that it wasn't affecting our lives in some way."

But Meir said that looking back at the planet from the station's orbital perch did offer a unique perspective on the unfolding situation, and she cited examples of astronauts who were in space during other major events in history, including the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001.

"There was actually a cosmonaut on a space station during the collapse of the Soviet Union, so he launched as a Soviet citizen and then came back and was wearing a flag that really no longer existed," Meir said. "But this, I think, was even more extreme, just because it literally was affecting every human, every country."

Meir emerged from NASA's quarantine last week, but she now finds herself in another form of social isolation — one that people around the world have been coping with for weeks and, in some cases, months.

As a self-described "hugger," Meir was looking forward to reconnecting with family and friends, but those plans are on hold. And although her training has taught her how to cope with isolation — living and working 250 miles above the planet in an orbiting laboratory roughly the length of a soccer field — the experience of social distancing is markedly different on the ground.

"Here, it's just so different, because you're not used to being isolated on Earth," she said. "That's not the way our society is built. So, to me, this is a lot more difficult to deal with, particularly after being gone for so long."

Yet despite the curveball of returning to Earth during a global health crisis, Meir described her mission as a dream come true. During her 205 days in space, Meir made history in October by taking part in NASA's first all-female spacewalk with fellow astronaut Christina Koch.

At the time, Meir was focused mostly on executing all the complicated steps of the spacewalk, but she said the subsequent outpouring of public support helped her and Koch understand the significance of the milestone.

"It would have been an amazing spacewalk no matter who I went out the door with," she said. "But it really wasn't lost on us how important it was as an event, how noteworthy it was as an event for people — actually much more so than I would have ever anticipated. I was really quite overwhelmed to see that response, and that was very humbling and really meant a lot to us."